The Life and Times of a General Surgeon

CONTENTS

PHOTOGRAPHS

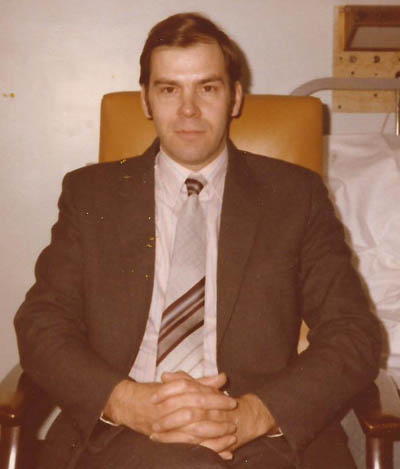

1. 1999 The author photographed by Rayment Kirby.

2. 1963.The Pembroke College Barge on the Isis, re-produced by kind permission of the Master, Fellows and Scholars of Pembroke College, Oxford.

3. 1967. St Thomas’s Hospital Boat Club Four.

Also by the author:

The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery. 1870-2000.

The Training and Practice of a General Surgeon in the Late Twentieth Century. 2014.

ISBN: 1499531370. ISBN 13: 9781499531374. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014908865. (To be found on Amazon as soft back book or Kindle version).

CHAPTER 1: Seven years as a medical student.

In the autumn of 1962 I went up to Pembroke College, Oxford to read medicine. The academic side of life has already been described*.

Pembroke College, formerly Broadgates Hall was founded in 1624 by letters patent signed by King James and was named after the Earl of Pembroke. It was one of the University’s smaller colleges. A friendly place with beautiful quadrangles covered by ancient ivy and set off by window boxes overflowing with flowers in the summer. The college was affectionately known as “Pemmy”. Tom Tower, the magnificent entrance to Christ Church, looks straight down on Pemmy whose walls were black. Then in the nineteen-sixties the blackness was a relic of the smoke and soot of the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, this soot had earned Pemmy the soubriquet of “Christ Church’s coal-scuttle”. By the 21st century all that grime has gone, the ivy removed and the walls restored to a pristine condition, the window boxes in summer are still stunning.

My rooms were on the fourth floor of staircase six of Chapel Quadrangle, sometimes called the second quadrangle, which was next to the Hall and the cellar. It could not have been more conveniently placed as friends would drop in for a chat on their way to hall for dinner. The atmosphere in the quad was succinctly summed up by John Betjeman, in his poem. ‘Summoned by Bells’, that was first broadcast in 1976, fourteen years after I had inhabited the top room on staircase six in second quad:

How empty, creeper-grown and odd

Seems lonely Pembroke’s second quad

Still, when I see it, do I wonder why?

That college so polite and shy

Should have more character than Queen’s

Or Univ, splendid in the High.

So for my first year I was the happy denizen of a large sitting-room cum study looking down on the second quad. There was a bedroom and a scullery at the back with a separate staircase for the scout to use. My scout, George Dawson, was the best there was. George was discreet and didn’t tidy up any papers even if they had been carelessly “filed” all over the floor. He brought a cup of tea in every morning and imparted any news he thought worthy of mention. If a visitor came when he was around, he would just melt away.

Years later in nineteen-sixty-nine, when I was collecting my degrees of Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery and then also eleven years later in nineteen-eighty when I received a Doctorate of Medicine, it was George who arranged the hire of the gowns and brought them to the Sheldonian Theatre for the degree ceremonies.

I joined the Boat Club and rowed enthusiastically. The Pembroke VIII had not been Head of the River since 1873. Now ninety years later in 1963 the VIII was languishing in the second division. In 2010 I had occasion to write a letter to the then Captain of Boats returning two books that I have had in my possession for many years. The History of the Rules and Regulations of the Pembroke College Boat Club, dated 1907 and the second was the Rules and Regulations of the Pembroke College Boat Club, printed in 1851.

On the final day of Eights Week races in 1964 the Pembroke Barge splendidly, painted in the college colours of cerise and white and moored to the bank of the Isis almost opposite the University Boathouse had a spacious deck which was ideal for watching the Bumps (races), being several feet above the waterline and so giving a clear view down the river. That day the deck of the barge was crowded with spectators.

As the boats of the first First Division, the final race appeared, everyone rushed to the river-side rail to get a better view. Suddenly there was an almighty crack as one of the mooring chains gave way and then a few seconds later the second chain also snapped with a loud crack. There was now nothing to hold the Barge and with the weight of the surprised spectators on deck, the barge started to list into the Isis.

I suddenly realised that as Captain of Boats I was in charge and as by now the Barge was listing at about fifteen degrees. I gave a great roar and ordered everybody on the deck to move without running to the riverside of the deck and start an orderly disembarkation. I must have done something right as all complied and reached the safety of shore. The listing continued and the barge came to rest on the bottom of the river at about 30 degrees. It was a sad sight to see the elegant old boat taking in water, but I was relieved that there were no casualties.

The day after the sinking, I revisited the poor old barge and waded along the upside of the stateroom to the cabins at the stern. A locker in the riverside cabin was dry and on opening it these two books were lying on the top shelf which is how I came to possess them.

We did enquire about repairing the barge, but alas the rather small sounding five thousand pounds needed in those far off days was beyond our means. I do not know what happened to the barge. Perhaps someone restored it lovingly and it is still gracing a stretch of the Thames.

During one of my long vacations I was in need of some money so I rang the pathology laboratory at St Thomas’s Hospital and asked if they had any work I could do. To my surprise the answer was yes and I became one of the laboratory’s porters. Instructed to collect all the specimens of blood and other fluids from every ward and outpatients and then deliver them to the laboratory, being fit I did this daily at the double. Then I distributed syringes and needles to the wards as the next task. This was quite heavy work as all the syringes and plungers were glass and were daily re-sterilised in an autoclave after being washed. The needles were also auto-claved and then hand sharpened. From personal experience I can say that even when sharpened they were blunt and painful for the patients. It was some years before the disposable sharp needles and syringes were introduced. I enjoyed a few weeks doing this and earned a little money. Another benefit was I now knew my way to every part of St Thomas’s Hospital, from the wards and laboratories to the subterranean passages, so I knew my way around before I would return in the different role as a clinical student.

There was interesting work going on in the science labs in Oxford. For example, the talk of the Anatomy and Pathology departments in 1963 was the work of Dr J.L. Gowans and E.J. Knight2, later published in 1964.

The problem that they solved was the conundrum of what happens to small lymphocytes (white cells) in response to an infection. It was known that these leave the bloodstream, by traversing the walls of the capillaries to reach an area of infection and then later collect in the regional lymph nodes (glands). What happened to them next?

In an elegant study in rats, Gowans and Knight showed that the small lymphocytes then pass along the lymphatic vessels which join together to form the thoracic duct which discharges the lymph and lymphocytes from most of the body into the left subclavian vein in the neck and so are recirculated in the blood stream. This is important, as although most lymphocytes have a short lifespan some are long lived and provide the immunological memory of past infections, enabling a rapid response to any repeat infection. This work established that lymphocytes circulated through the lymphatics and back into the bloodstream**.

After being awarded a degree in Animal Physiology and passed the preclinical examinations I went as a student to St Thomas’s Hospital in Lambeth in London on the edge of the Thames looking directly across at the Houses of Parliament.

I had the pleasure during the years of clinical study to live at 19 Middleton Square near the Angel of Islington. Middleton Square is a Regency Square with imposing terraces of houses on the four sides of the square, with most houses having five floors. Number 19 has a small patio and garden at the back and at the top of the house the roof was flat, easily accessible and ideal for sitting out on. The house had five spacious bedrooms, a magnificent sitting room on the first floor, a large dining room on the ground floor at the front with the kitchen at the back. There were also two bathrooms and three lavatories. I still marvel that a bunch of students managed to find such a fantastic residence in an elegant house now worth a fortune. Perhaps not, for when I walked in Middleton Square in 2014 I saw that number 19 had been converted into flats and the house looked down at heel.

Residence in this Regency terraced house was made possible by my friend, Paul Clarke, also a medical student, who had been at Oxford. While there he had joined the Royal Navy. On coming down from Oxford he was a Surgeon-Sub-Lieutenant and with the Royal Navy behind him was an ideal tenant for the New River Company who owned Middleton Square and thus obtained a lease on the house.

Paul invited four fellow students to join him. Andrew Pengelly and Andrew Hillyard who had been at Keble College, Mike Mole and I were from Pembroke College. The two Andrews and Mike were clinical students at the Middlesex Hospital, I was at St Thomas’s Hospital known as Tommy’s and Paul was at Bart’s, St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

We arranged to pay £5 2s 6d a week (£5.12 ½p) into a special account in Paul’s name. This covered: the rent, basic foodstuffs, local phone calls and utility bills. There was still enough money left over for one or two parties to be held at the house every year. I do not remember any arguments at all arising from this arrangement, it was very harmonious. We were a fortunate generation as parents paid tuition fees and students whose parents could not afford these fees were given financial help after submitting to a means test and so received a grant from their local County Council, who were generally most supportive. The present system of loans, in the twenty-first century is daunting for modern students, for whatever degree they get they are guaranteed to be in debt when they graduate. A small counter balance in the nineteen-sixties was the low salary of a house officer. After tax and paying for housing the net income was fifteen pounds a month and only a year or before house officers were not paid.

St Thomas’s arranged an introductory course for all new clinical students which lasted six weeks. Oliver Stansfield had been a year ahead of me at Pembroke and had gone to Tommy’s the year before. He told me that there was no need to attend all the introductory course as everything would be covered later. Sadly, Oliver who was an experienced and keen mountaineer, died tragically from a fall in the Alps a year later, a very sad loss.

Having presented myself to the Dean of the Medical School, Mr. R.W. Nevin, I then spent much of the next six weeks on the Thames rowing. I came to know the members of the Hospital Boat Club well and after rowing in various races formed a coxless IV with Rod Thomas, John Black and Richard Collins. The next year this same crew rowed in the ‘Wyfold Fours’ event at Henley Royal Regatta and we did reasonably well. Not having had time to train as much as we would have liked we were satisfied with the result. Years later John Black became well known as the President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

These few weeks of the introductory course at St Thomas’s was an idyllic interlude between undergraduate and clinical studies. Looking back, it was the longest break from intensive study or work I had until my retirement.

The clinical year was very different from university terms and was continuous with no formal vacations. Each student could take two weeks holiday a year. My parents being abroad during my student days I lived at 19 Middleton Square throughout this time, except when on ‘take’ and living in the hospital one week in four.

I have written about the excitement and broad experience gained as a student while living in the hospital in ‘The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery***’

It was not all hard work and one night when the emergency work had settled down and no-one else was around, three of us played a game in the nineteenth century part of the hospital. We rolled golf balls along the wide and very long corridor on the ground floor of the hospital and the one who rolled it farthest without touching either wall won. This game brought to mind the brilliant architecture of this older part of the hospital.

St. Thomas’s Hospital, thought to have been founded in eleven-seventy-three when Thomas a Becket was canonised, was finally settled on its present site on the bank of the Thames opposite the Houses of Parliament with completion of a new building in eighteen-seventy-one. It consisted of six blocks on three floors, housing out-patient clinics, wards, operating theatres and everything else needed for a hospital, all connected by a single very wide corridor on the ground floor, running the whole length of the building.

This thoroughfare carried all the pedestrian and trolley traffic of the hospital as it was necessary to use this corridor when walking from any part of the hospital to any other. This was a very useful and natural place for casual clinical meetings. For example, two surgical firms with their students while going about their business from one hospital block to another, would cross paths on the ground floor corridor, then stop and talk about patients and topical subjects of mutual interest concerning surgery. The point being that the corridor was wide enough for such a meeting with up to twenty people to take place without obstructing the flow of other people going about their business. It worked brilliantly. It does not translate into modern buildings which are vertical and all movement within the building is by lifts and staircases which do not lend themselves to useful patient orientated casual discussions.

Student days at St Thomas’s while living in Middleton Square were good. Although very busy there was time to study other things and among my interests was the ever growing population of the world.

References.

*The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery. 1870-2000. The Training and Practice of a General Surgeon in the Late Twentieth Century. ISBN 1499531370. Published in 2015 by Amazon. The academic side of life in Oxford is described in this volume.

**J.L. Gowans and E.J. Knight. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences, Vol 159, No 975, (Jan 14, 1964). Pp 257-282.

***Thomas Fairchild (1667-1729). In 1717 Fairchild took pollen from a carnation and inserted it into a Sweet William resulting in successfully fertilisation. The resulting plant was the first recognised man engineered hybrid plant and became known as ‘Fairchild’s Mule’. This caused great interest and a paper was presented to the Royal Society in 1724. Philosophical Transactions (XXXIII. 127). It also caused problems with the Church due to the belief in creation and therefore the immutability of species at that time. Fairchild kept a vineyard and plant nursery in Hoxton, London where the school was named after him.

CHAPTER 2: A houseman’s life.

The lease at 19 Middleton Square finished when student days finally ended. Having been undergraduates at Oxford we returned there for our final examinations in medicine and surgery. Successful in these examinations, the letters BM, BCh, (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) could be added to the BA in Animal Physiology already awarded. Now a graduate could be called by the honorary title of Doctor.

At the ceremony in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, those being awarded degrees in Medicine swore the Oath attributed to Hippocrates (460-377 BC) philosopher and physician. This oath lays down the moral code of conduct for doctors. The oath was read in Latin with a cadence and great solemnity. In an august place, surrounded by one’s fellows and a great congregation it was impelling and we all answered “Volo” in loud voices meaning, “I will*”.

My first day at regular work was at the age of 24 when my friend Patrick Wheeler and I were appointed as house surgeons to Mr R.W. Nevin and Mr H.E. Lockhart-Mummery. Mr Nevin was known to the students and junior doctors as “Uncle Bob” and as he was Dean of the Medical School of St. Thomas’s Hospital, this was a prestigious job and I was lucky to have it.

During the week Mr Nevin lived in a flat in Lambeth Palace, just a short walk from the Hospital, and at weekends went home to the country. It was his habit to come into the hospital every weekday at eight o’clock, to be met at the front entrance by the house surgeon who had been on duty the night before and then together, conduct a round of all his patients.

I lived in the hospital for over three months out of my six months as house surgeon. This was because Mr Nevin’s Firm was on ‘Take’ one week in four when both house officers had to live in to look after the emergencies, so I lived in the hospital for fifteen of the twenty-five weeks that I served as a house surgeon. The work done is detailed in my book**.

A pleasant feature of “living in” was eating in the Junior Doctor’s Mess, which was quite luxurious at that time. We sat at long tables, elegantly laid, with stewards serving at meal times. The chef was excellent and his special delight was to produce a fine dinner for special occasions. The resident junior doctors held one mess dinner while I was “on the House”. It was a splendid affair which matched anything a good hotel could produce. All hospital doctors who were not consultants were called “junior doctors” even if forty years of age and about to be appointed as a Consultant.

Also while on the house I had my first introduction to private practice. Mr. Nevin’s private patients were admitted to the tenth floor of the new hospital block and it was my duty to clerk and admit them and then write up progress notes during their stay. I never had the impression that Mr. Nevin had a large private practice but the patients who came under his care were usually well known.

One morning my bleep gave out the emergency call requiring immediate attendance. The message on my bleep simply read, “Ward 10”. My heart bounded as the only patient Mr Nevin had on Ward 10 that week was Mr Harold Macmillan, the former Prime Minister. I ran down the corridor of the old hospital blocks to the lift and quickly reached Ward 10 on the tenth floor of the new casualty building. On the way I had been turning over in my mind the most likely emergencies that might have befallen Mr Macmillan since his operation a few days before. Heart attack, pulmonary embolus secondary to a deep vein thrombosis or reactive haemorrhage following the operation were the most likely candidates. If he had suffered a cardiac arrest, then the medical “cardiac arrest team” would have also been summoned.

During Mr Macmillan’s operation, a few days before, I had been second assistant, holding a retractor for Mr Nevin at the cholecystectomy he had carried out. The first assistant was Mr H.B. Devlin an able and experienced Senior Registrar. The operation was difficult due to dense chronic inflammation that often occurs in an inflamed gallbladder. The operation had been completed without any problem.

On entering Ward 10 I went straight to Mr Macmillan’s room which had a splendid view across the Thames to the Houses of Parliament on the opposite bank. Just as I was a few paces away the senior consultant physician stepped out of Mr Macmillan’s room holding a large vase of flowers which he handed to me saying, “Ah. There you are Maybury, take these flowers away, Mr Macmillan has too many in his room”. To my breathless enquiry about Mr Macmillan’s wellbeing, he gave me a quizzical look, expressing the sentiment of “silly boy” while he said, “Fine”. I replied, “Yes sir”, and did as I was told with a smile not being sure which emotion was uppermost in my mind, relief that no disaster had befallen Mr Macmillan or chagrin at being summoned by emergency bleep to sort out the flowers!

Mr Macmillan was a good patient and no word of distress or complaint crossed his lips despite his discomfort. He did tell me, a few days after the “flowers” incident while I was carrying out my routine late evening visit of all the firm’s patients, that he had a sharp pain in his lower abdomen. His observations were all stable and he looked well. I carried out a careful abdominal examination and as with any other patient a PR examination. There was nothing the matter that minor treatment would not solve which I duly administered.

The next morning at eight I met Mr Nevin at the main entrance and as we walked through the hospital to the wards I told him what I had found and done for his patient on Ward 10. Mr Nevin’s pace slowed down and he gave me a hard look but said nothing. He may have thought that I had gone beyond my remit, but on finding Mr Macmillan cheerful and his pain gone, probably reflected I had only done what housemen were taught to, and ought to do. The matter was not mentioned again.

On another occasion when I visited Mr Macmillan he was very genial and asked me about my career and as that topic of conversation lapsed I ventured to ask whether he regretted no longer being in the House of Commons over the river. “No”, he said, “I’m too old for playing games” and laughed. A few weeks later he was seen on television getting into a taxi, possibly his first outing since his operation and a reporter asked. “How are you Sir”, and after a pause while he thought about it he replied, “Considering the alternative, very well!”

Another of Mr Nevin’s private patients was an Iraqi Air Force General who arrived bringing his own physician with him. I assisted Mr Nevin at the operation on the General and noted that the general’s personal physician insisted on changing and joining us in the operating theatre. He wanted to inspect every stage of the operation and doubtless reported back to the General when he had recovered from the anaesthetic. We were never told the reason for the Iraqi physician’s detailed interest. The Iraqi General gave me a bag of pistachio nuts when he departed for home. A rare treat at that time.

The people of Lambeth in the nineteen-sixties tended to delay seeking help from the hospital for serious surgical problems, such as obstruction of the bowel or acute appendicitis, so it was not uncommon for them to appear in casualty several days after the onset of their condition.

Thus those with obstruction had not infrequently perforated their colon by the time they attended hospital and had severe peritonitis. Due to the seriousness of their condition they were taken swiftly to the operating theatre after rapid intra-venous rehydration whatever the time of day or night. The most popular time for the sufferer to finally give in and come to hospital for help was often late on Friday afternoon. Fortunately, a full service was given at any time of any day of the week, including public holidays.

Assisting at these operations the surgeons always wore a plastic apron under the sterile surgical gown. On opening the abdomen, the foulest stench would fill the theatre and brown liquid would usually pour out. Surgery was kept to a minimum as the mortality of these patients was high so the perforated bowel was resected and the ends brought out as one or two colostomies. The abdomen was carefully washed out with an antiseptic and antibiotics started. If the patient survived and the perforation had been caused by an obstructing cancer of the colon this would be resected a few weeks later, when the patient was fit enough to withstand a more major procedure.

In cases when the appendix was excised it was frequently gangrenous and therefore septic which meant that development of a post-operative pelvic abscess was common. Mr Nevin managed these patients on the ward. The patient would develop a fever and lower abdominal pain. Any such patient was examined by Mr Nevin on his ward-round and the examination included a rectal examination. At first he would often say, “It’s not ripe”. Over a few days the abscess, a collection of pus, would begin to “point”, developing a softness of the rectum where if left alone it might spontaneously rupture. It was safer to drain the abscess surgically.

Then at his next examination Mr Nevin would announce, “Its ripe, sister the scalpel”. The Ward Sister would quickly come back with one. The blade of the scalpel was laid along his index finger so the tip did not protrude. He would pass his index finger with the blade protected into the rectum. He could then feel the abscess bulging down into and compressing the rectum. With the tip of finger on the softest part of the bulge he would slide the scalpel forward into the abscess and then withdraw both blade and finger. Sister had a large kidney dish ready and placed it against the patient and the pus would pour out. This could be up to three quarters of a litre of pus. The patient immediately felt better and as the fever subsided very quickly they were usually ready to be discharged next day and now draining freely the abscess cavity would heal spontaneously. This was a technique I used on such a case as a consultant myself, this complication having become very rare due to early presentation of patients with appendicitis and prophylactic use of antibiotics during the operation when the appendix was removed.

Another process I learned and saw how to manage was the infection and breakdown of the perineal wound following excision of the rectum for severe ulcerative colitis or cancer. In these circumstances the sutures were removed and the wound opened and then washed with antiseptic and packed with gauze, damp with antiseptic and liquid paraffin. These packs were changed daily at first and care was taken to ensure that no pockets of pus remained. Eventually the wound would heal perfectly without any further surgical intervention. Very occasionally, years later, I used this slow, old fashioned but safe technique to heal infected perineal wounds.

All Mr Nevin’s house surgeons were instructed at the beginning of their tenure, that if a Lady from the Palace rang concerning any member of the Queen’s Household with a surgical problem the answer to any request made was to be automatically answered with a, “Yes Madam”. The patient must be admitted immediately and Mr Nevin informed. He was Surgeon to the Queen’s Household and also to the Metropolitan Police, so any

request from this latter quarter was to be responded to similarly.

To progress my career as a budding surgeon the first professional examination had to be negotiated. This was the Primary examination for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) which could only be sat following the statutory completion of two house officer posts of six months each, one attached to a surgical firm and the other to a medical firm, then post a casualty officer post (Accident & Emergency Senior House Officer) for six months.

Mr Nevin advised me to apply for a casualty officer’s post at St Thomas’s which would last for six months to be followed automatically, if my application was successful, by six months as a Prosector in the Department of Anatomy of the Medical School. I applied, this was a written application without interview as Prosectors were all appointed from within the Hospital. I was very glad to have been successful, not only because it was a good post but, also I had secured employment for a further year provided I could find a house physician’s post first. There was never any security of tenure, or pre-arranged progression of appointments to jobs throughout my training.

I mentioned my immediate problem to Brendan Devlin, the senior registrar, who was very helpful and thought that Dr Peter Reed, a Consultant General Physician with a special interest in gastroenterology who worked in Slough was looking for a house officer and he would give Dr Reed a ring. With this recommendation Dr Reed asked me to attend for an interview at Wexham Park Hospital.

The interview was an informal affair. I arrived on time exactly as instructed and found that Dr Reed was about to start a routine ward round of all his patients and I was to join it.

The doctors on the round were Dr Reed, Dr Prakash his registrar, the house officer, a couple of students, the Ward Sister and me. We went from bed to bed to see the patients and I was asked one or two straight forward clinical questions. What was particularly interesting was the range of conditions from which the unfortunate patients were suffering.

There was a patient, just admitted, with severe untreated thyrotoxicosis with cardiac complications. Several others had ulcerative colitis, one a sprightly ninety-year old lady was having a first attack of this disease. Her diagnosis was confirmed during the round because fibre optic endoscopes were just becoming available and Dr Reed had one which was used in a side ward set aside for the purpose. The lady was duly scoped under sedation to about 30 centimetres from the anus and all on the round got to look down the scope at a typical florid inflammation of the inflamed rectum and sigmoid colon.

Two patients were recovering from heart attacks and one stroke patient was also reviewed. Then there were patients with severe problems caused by diabetes, two being treated for very high blood sugars, hyperglycaemia. Also a patient recovering from a severe episode of extremely low blood sugar or hypoglycaemia. I was very interested.

After the round we had tea in the Ward Sister’s office and when everyone else had dispersed to their routine duties Dr Reed interviewed me. He asked what my career hopes were and what I had been doing at St Thomas’s. This lasted about ten minutes and then he said he had to go and as he was leaving told me I had been appointed. Just like that. This was 1969 and this was how house officers were appointed until the early 1990’s when interviews began to be more formal and arranged centrally.

Wexham Park Hospital on the outskirts of Slough was fairly new, having been opened in 1965 when its design won the architects a prize. The hospital consisted of a central tower seven stories high, with single story arms radiating out like spokes of a wheel from the base of the tower. The doctor’s mess was on the sixth floor of the tower block and the doctor’s residence on the seventh, a splendid place with huge plate glass windows and panoramic views. At the planning stage the hospital consultants saw the plans and were asked for their views. Most were silent but one ENT surgeon asked where the helicopter-pad was to be situated. There was silence among the architects and then one said, “We hadn’t thought of that!”. Wexham Park Hospital was, I believe, the first hospital with an integral helipad!

When I joined the hospital junior staff and was on duty, my room was on the seventh floor When bleeped for an emergency during the night I rushed to the lift and while it descended seven floors put on my trousers and long white coat over my pyjamas and ran to the site of the emergency in my bare feet. It rarely took more than a minute to run and so emergencies were always attended to very quickly. There was one patient who was very grumpy, who noticed that my pyjama top was showing and said “What are you doing sleeping on duty? Aren’t you the night doctor.” To which I replied “Yes and the day doctor too”.

The mess was very lively and there were frequent communal dinners with each course produced by a different person. In view of the international composition of the mess we had splendid food of all types from Europe and Asia. My wife, who was a teacher at a local primary school, organised this and when the time came to leave our friends at Wexham Park and move on, it was proposed at a mess meeting that someone should be found to fill her unofficial post as mess co-ordinator!

When not on duty, the two weekly rota allowed two nights off the first week and three the second, for this we had been allocated a semi-detached house in the village of Ivor Heath not far from the hospital. When we first went to the house the front garden looked neat and the grass was recently mowed and it looked promising.

On opening the front door, a waft of freezing damp air greeted us. The carpets were filthy and on entering another smell, this time of stale cooking became apparent, there was no central heating and we hastened to light a fire in the sitting room. There was some damp coal but nothing that would light it, so we next turned our attention to getting some hot water which was heated by a solid fuel boiler to be lit by a gas poker. Sara struck a match to light the poker and there was a small explosion. Fortunately, Sara was not hurt but there was now no way of heating any water.

The back garden was a shambles, no-one had tried to do anything with it for years. We later discovered that our neighbour, a kind man who suffered from shell shock following the war, was in the habit of keeping our front garden in order, without recompense, because it was a doctor’s house.

The next day my wife rang the hospital secretary’s office to see if a new boiler could be installed, only to be told, “No, because the next tenant might not want hot water”. The logic of this eluded us. Having bought some dry coal and using old newspaper we lit the sitting room fire. Whenever we were in the house, when I was not on duty, the only heating we had was this fire. We had by now removed the decomposing food from the cooker. Every weekend when not on duty we escaped and went to stay with Sara’s parents in the beautiful village of Brightling in Sussex. There we were warm and always made most welcome.

One evening there was a lecture given in the mess by Professor Sir Ian Coote and afterwards I went to speak to him. We had met fourteen years earlier, in Kampala, where he was the Minister of Health in the Colonial Government of Uganda. I was eleven years old when I told my parents that I wanted to be a surgeon and in view of this ambition my father took me to see Professor Coote to discuss what path I should follow to achieve this. The Professor was very kind and told me about the great Teaching Hospitals in London, mentioning particularly St Thomas’s Hospital opposite the Houses of Parliament. That evening at Wexham Park I was able to thank him for his advice and let him know that I was making progress in my ambition and had been a medical student at St Thomas’s.

Reference.

*If the reader wonders whether the new graduates knew what they were agreeing to when affirming the Hippocratic Oath, he or she will be reassured that all were given a translation before the ceremony.

The original oath reads:-

I swear by Apollo Physician, by Asclepius, by Health, by Panacea and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture. To hold my teacher in this art equal to my own parents; to make him partner in my livelihood; when he is in need of money to share mine with him; to consider his family as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture; to impart precept, oral instruction, and all other instruction to my own sons, the sons of my teacher, and to indentured pupils who have taken the physician’s oath, but to nobody else. I will use treatment to help the sick according to my ability and judgment, but never with a view to injury and wrong-doing. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course. Similarly, I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion. But I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art. I will not use the knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone, but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein. Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick, and I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, especially from abusing the bodies of man or woman, bond or free. And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession in my intercourse with men, if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets. Now if I carry out this oath, and break it not, may I gain for ever reputation among all men for my life and for my art; but if I transgress it and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.

(Note by the author. The Hippocratic oath has been rewritten many times but seems to get more complicated. In this translation it appears that the practise of abortion is forbidden but it is now legal in the UK. It is thought that a particular means of procuring abortion has been proscribed by Hippocrates, while abortion itself was carried out in those times. Nowadays a doctor must abide by the ethical and legal demands in such a case).

**The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery. 1870-2000. The Training and Practice of a General Surgeon in the Late Twentieth Century. ISBN 1499531370. Published in 2015 by Amazon. The academic side of life in Oxford is described in this volume.

CHAPTER 3: House hunting and tales from casualty.

Once back at St Thomas’s, working as a casualty officer, Sara and I started to look for a house to buy. We were rather naive as between us we had no capital. Not surprisingly after enquiring at several Building Societies, it became apparent that none would give us a mortgage without a ten percent deposit. This seemed to be the end of our aspiration to own a house. Although salaries were small in 1970, it was an era of prosperity with virtually full employment and property especially houses were appreciating in value fast. It was a desirable time to own your own house.

Since leaving Iver Heath, near Wexham Park Hospital , Sara and I were staying with her parents while I commuted to London to work. On my first weekend on duty in casualty, Sara was with her father having a drink in the Swan Inn at Wood’s Corner in Dallington in Sussex. While standing at the bar she was talking to the landlord about the difficulty of getting a mortgage when a man standing next to her introduced himself as Brian French and told her that he might be able to help with a mortgage provided she did not mind borrowing from a Building Society based in Ireland.

This was good news, as we rather fancied living in a picturesque farm house situated locally. Hook’s Farm was old and built in the classic Sussex style with facing tiles on the upper story. However, it was in a very dilapidated condition and in need of much restoration. This property was mentioned to Brian French and that it was for sale at six thousand pounds. he laughed and gently dashed this dream by saying that no building society would lend to an impecunious pair of young people against such a risky property.

Building Societies, he said, would only lend against new houses which could be easily sold. He knowledgeably added that if one bought the first habitable house on a brand new estate, then by the time the last house was built and ready for sale, the price would have risen, so increasing the value of any houses bought first. Brian French then asked where we wanted to live and Sara thought within a short commute from Waterloo Station, perhaps up to a maximum of an hour’s journey to allow me easy access to St Thomas’s Hospital. A few days later we met Brian at his office in Robertsbridge. He had taken a lot of trouble on our behalf and showed us a map of London and the South East on which he had marked Waterloo Station and three new housing developments he had identified. All these estates had just started to be built and were within forty minutes by train of Waterloo Station.

We visited all three estates, but the one which really caught our eye was in Gillingham in Kent, where for three thousand nine hundred pounds a three bed-room terraced house with a separate garage could be purchased. Brian had more good news in that he had arranged a mortgage in principle for us to buy such a property with an Irish Building Society. We never did find out why he thought we might object to an Irish Building Society.

The Gillingham house was an attractive little house with a kitchen-dining room, we had the floor tiled in black and white. The sitting room was at the front with three minute bedrooms upstairs and a tiny fenced garden at the back. It was perfect and we bought it with the mortgage arranged by Brian French for the price quoted.

The day of the move we arrived at the house and waited for the van to arrive with our furniture. By evening nothing had happened and I was unable to contact the removal firm. Fortunately, the house was carpeted but even so we spent a very uncomfortable night especially for Sara who was pregnant. To my relief the furniture arrived the next day. We had bought the second house to be sold on the estate, exactly as anticipated by Brian French its value rose during the following twelve months as the estate was duly completed and all the houses sold. Because the estate in Gillingham was well placed and a pleasant place to live, our house, as predicted sold very quickly for four thousand nine hundred pounds. Now thanks to Brian French we had a respectable deposit for our next house. We were very grateful to him and met him often at the Swan Inn over the next few years.

Sometime later he offered us a house in the main square in Assisi in Italy for six thousand pounds as a holiday house or to let. This was unfortunately beyond our means and regretfully we were not able to take up his offer. The experience of buying a house combined with the mess I had made of the removals whetted Sara’s interest in houses and thereafter she proceeded to buy and sell our subsequent houses, seventeen in all, arranging everything including all the packing and removals.

We liked living in the Gillingham house and were very happy there. It was to this house that our first child, Nicolas, was brought home to after his birth on the second of December nineteen seventy at the General Lying in Hospital in Lambeth. When Sara went into labour we were staying with friends in London so it only took a few minutes to reach the hospital.

It was early evening but very dark inside the hospital as there was no electricity, this being a time of the three-day week, power cuts and refuse piling up in the streets. Once Sara had been admitted, a rather harassed young doctor came in who I knew vaguely. He said he was rushed off his feet and asked me to put a drip up on my wife as he didn’t have time. I was surprised but did as he asked. Then the midwife came in and happily within a short time Nicolas was born. As was customary Sara stayed in hospital for several days. Then we returned to Gillingham delighted with our first child who was a fine boy.

Working in Casualty (Accident and Emergency Department) was interesting, sometimes amusing, and at times tragic. It was the only training post in those days which was worked in shifts, being the only hospital job which did not provide continuity of care as all the patients were either sent home or admitted under the relevant specialty.

Late one Saturday afternoon, when I was one of the Casualty Officers (CO) on duty, two large rugby forwards from the Tommy’s First XV came into casualty together, one with his two front teeth missing and the other with puncture wounds on the top of his head. Have cleaned the latter’s wound and probed the twin scalp punctures; I was surprised to find the missing teeth embedded deep in the scalp. They were in good condition and after extracting and washing them carefully I gave them back to the “toothless” one to take to his dentist. We all had a good laugh especially the casualties. Those were the last years that the St Thomas’s Hospital rugby XV with an England cap in the side, had fixtures with first class clubs including Rossyln Park and the London Irish.

On another occasion there was a sad tale to tell with an unexpected coincidence. One afternoon the telephone rang to say a casualty with a cardiac arrest was being brought in from Waterloo Station. It was normal practice at that time for a CO to go out the forecourt to meet the ambulance and take immediate charge of resuscitation. On the stretcher was a man of about forty who had had the cardiac arrest. I took him to the resuscitation room and made every effort to revive him but to no avail and in due course declared him dead. It transpired that the lady with him was his secretary and she had been seeing him off from Waterloo Station when he had collapsed on the platform. A tragic situation. she insisted on ringing the man’s wife to tell her what had occurred in spite of my offer to do so.

While serving as a casualty officer I was the junior doctor’s mess secretary and so involved in arranging parties and dinners. The doctors from the previous year had departed from the hospital after a terrific end of job party and had omitted to pay the drinks bill of over one hundred pounds to the wine merchant. The new occupants of the mess were none too pleased, but we honoured the debt and paid the bill.

I organised a formal dinner about half way through the job. We invited my former chief Mr Nevin and his wife as the guests of honour. The chef excelled himself and the Nevins greatly enjoyed the occasion and stayed till late. I received a note of thanks from Mr Nevin, which said how much they had enjoyed the occasion, adding that this was the first time they had been to a mess dinner given by the junior doctors.

Each new batch of casualty officers were given a half day off and treated to go “Round the Corner”. This is an obscure way of saying that we were given a guided tour of the Metropolitan Police’s Black Museum of Crime. This was a great privilege as the museum was not open to the public and only available to police officers and invited guests. This visit had been arranged by Mr Nevin, as Dean of the Medical School, who as previously mentioned was surgeon to the metropolitan police.

I am just old enough to remember when the famous and very distinctive white five-pound note was legal tender. Displayed in the museum alongside a genuine white five-pound note was a forgery, which on a casual glance looked real. The story was that the forger was a racing addict. When he ran out of money for his next bet he secreted himself in a lavatory and there took a pre-prepared sheet of white paper of the right size and about the correct texture from his pocket and then drew in black ink a new note from memory, in a few minutes he had a note which was passable as legal tender in the rush of placing a bet with a bookie at the racecourse. Good at drawing he might be, but not very clever as he only managed to pull the stunt a couple of times before being caught and had won nothing. There were other more sinister exhibits concerning famous murders in London.

After six months in Casualty I moved to the Anatomy Department in the pre-clinical part of the Medical School as a Prosector of anatomy. The pay was meagre, but I was fortunate in that I was asked by Mr Frank Cockett’s secretary if I would like to assist Mr Cockett in his private practice during this time and was offered five pounds a leg. Mr Cockett was a general surgeon at St. Thomas’s, nicknamed “the Ace” by the students. The private practice I assisted him with was exclusively stripping varicose veins, hence my being paid by the leg. He operated several evenings a week, in various private hospitals in central London, between five and seven in the evening also occasionally on Saturday mornings. This fitted in very well with my work as prosector.

As was then the custom, Mr Cockett carried his own splendid gold plated surgical instruments with him, including solid gold needles. After sterilisation these latter were hand threaded by the scrub nurse, as this was before the era of atraumatic needles. His car had a number plate beginning with the letters VV and his sailing boat was called Saphena. Quite a charming feminine sounding name as befits a yacht, but in fact a saphenous varix is a significant dilatation of the highest part of the long saphenous vein just before it joins as a tributary the large femoral vein in the groin and is removed as part of the operation of stripping’ varicose veins. Mr Cockett had a good sense of humour.

Several evenings a week I assisted him at these operations and learned his operating technique which gave excellent results with good cosmetic effect. As Mr Cockett’s confidence in me grew, my assisting became more active and sometimes he asked me to close the wounds. The experience of working for Mr Cockett was of great value in my own private practice years later, but of that I had no inkling at the time. One Saturday morning we finished early and he took me to one of the auction houses in Bond Street to admire a picture he fancied of a nineteenth century oil painting of a splendid man-of-war. I expect he bought it at the subsequent auction as he was reputed to have a fine collection of naval paintings.

My six months as a prosector passed quickly and working again on cadavers and teaching students anatomy, honed my knowledge of the foundation science of surgery that served me well in the future. Since we used Gray’s Anatomy as our textbook one of my co-prosectors, John Black, found an error in Gray’s Anatomy and was proud to point it out to the Professor of Anatomy, Professor Davies, who was also the Editor of the next edition of the book.

CHAPTER 4: Experience in Warwick.

In 1971 I travelled to Warwick, having been invited to attend for an interview by Mr John Marsh, Consultant General Surgeon at Warwick Hospital. After meeting him I accompanied him on a ward-round followed by an informal interview and was appointed on the spot as his Surgical Registrar to be based at Warwick Hospital. There was one proviso, that I must pass the Primary FRCS examination to take up the post. I had already completed the jobs stipulated, by the Royal College of Surgeons of England as essential training and all that remained was to sit the exam. This was to test the knowledge of a candidate in the sciences underpinning surgery, anatomy, physiology and pathology. The examination took place at the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields only two weeks before Mr Marsh was expecting me to be in post.

Post graduate examinations in medicine and surgery are quite unusual in that the results are announced within hours of the last viva taking place. Following a short time waiting nervously, the list of candidates who has passed was posted on the notice board at the Royal College of Surgeons. I found my name had been included, I had passed and could now proceed to Warwick Hospital.

My wife and I had been offered the house usually allocated to the surgical registrar and after a very cursory look I had accepted it. In those days a single person would live in the house rent free, but being married a commercial rent had to be paid.

Just before my appointment started I went to Warwick to start work. Sara had meanwhile contacted an agent to put our house in Gillingham on the market. The agent said he actually had a waiting list of couples who wanted our house which was good news and confirms the buoyancy of the housing market at that time and the wisdom of Brian French as the house was sold very quickly.

There was only one surgical registrar at Warwick Hospital, who inevitably had great responsibility. Warwick Hospital was the only A & E department in South Warwickshire and all accidents and emergencies not only from the town but also from Leamington Spa and Stratford-upon-Avon, including the surrounding countryside were brought in by ambulance.

Sometime later having packed up the house Sara came up to Warwick from Gillingham. She travelled with the removal men in the furniture lorry, with Nick, our babe in arms and Jack our French bulldog. She told me that this experience was new to the removal men and that they were very kind to her and looked after her well on the journey. The alternative would have been a difficult journey by train with several changes in London with Nick and the bulldog.

On arrival in Warwick she saw the hospital’s semi-detached house allocated to me for what it was; dangerous to live in. Not only was it dirty, but the kitchen was only furnished with a large sink, which was chipped with an unhygienic draining board. There was no work surface and the gas cooker was dilapidated and rusting. That was the best part of the house. In the bathroom everything was chipped or cracked. The immersion heater had no thermostatic control, so the water was boiling all the time. The worst of all defects was a crack in the wall extending from the landing into the bathroom which was big enough to put a hand in. Last but not least our neighbour warned us not to put the baby outside in his pram as all the guttering was loose and at risk of falling. I had indeed been carelessly unobservant at my quick look round.

The following day, in a quiet moment, I told my new chief that we would not live in the hospital house and would move out as soon as we had found somewhere to buy. John Marsh was not best pleased. If I moved out what could he offer the next Registrar to live in, as the house was sure to be snapped up by another department. I quietly stuck to my guns and said the house needed extensive building work as well as refurbishment. After some weeks he did come and look round and agreed it was not habitable. I was now grateful that my wife, with natural flair, was arranging everything to do with our housing.

She quickly found and bought a bright, large and comfortable 1960’s house with four bedrooms, 1 Crossfields Road situated only one hundred and fifty yards from the hospital. We settled in quickly. Sara ran an open house for other junior hospital doctors and it was a most enjoyable place to live.

From the moment I started work the phone rang frequently day and night, especially from casualty and the surgical wards, when often a young female voice on the phone would say, “This is Clare Ward” when asking to speak to me. “Who is this Clare Ward who keeps ringing you,” Sara asked. The wards on which I worked were called Rylands and Clare Wards!

My work rota was awesome. In week one I was on duty all seven days, both day and night except for Wednesday afternoon. In the second week my duty rota was from Monday to Friday, day and night, but with the weekend off. Usually I could get away at six or seven on Friday evening. This two-week rotation was then repeated. This was a baptism of fire, but I enjoyed it enormously as under Mr Marsh’s careful tutelage I made rapid progress. I did not mind the hours as I was accumulating experience at a tremendous pace having arrived at Warwick with very little experience of operating. The work was all absorbing and very busy day and night.

There were many times that I started operating at nine in the morning and was still operating at midnight and often on through the night. The way this worked was by adding all acute surgical emergencies coming into casualty during that day and night to my ongoing operating list. Fortunately, casualty was only a few yards away from the operating theatre so between operations I would go and see the new admissions to casualty and there would be time to get any x-rays or blood tests needed before operating.

Looking back this was a most amazingly efficient way to look after patients, as those with acute appendicitis, strangulating femoral or inguinal hernias, perforated duodenal ulcers, acute bowel obstructions were dealt with within hours of coming into hospital. Initially Mr March was frequently in the hospital at night but as I rapidly became more experienced and his confidence in me increased he allowed me to proceed alone knowing I would ring him concerning any difficulty I may have. Within months these lists would now include patients with blood loss following road traffic accidents whose spleen I removed and carried out colostomies on patients with obstructing tumours of the colon. The full list of operations I learned to carry out in my two years at Warwick Hospital are listed in my book ‘The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery*’.

I loved these long lists as operating through the night was usually very peaceful as the interruptions only came from casualty and the hospital was otherwise quiet. Coming home at dawn on a fresh summer’s morning for breakfast was always pleasurable. I was glad that my wife and I had discussed the irregular home life before getting married and she had accepted it then, but now it was the real thing and all was well between us.

When I was late Sara always stayed up and waited for me and we always had a chat and then breakfasted together with Nick, our baby son. This was about the only time that I saw him regularly as I was rarely home before he went to bed. Then having shaved and bathed I was back to the hospital for the day’s work.

As was normal at that time no concessions were made or expected for sleep lost and no lists were ever cancelled because the surgeon had been up all night. I have frequently been asked if these long hours led to mistakes being made. I was never drowsy while working either on the ward, in casualty or in theatre as the work was so fascinating and all absorbing. I was never bored and remained fully alert when working whatever the hour. Being a surgeon is not the same as driving for hours when the monotony would get to a person resulting in overwhelming tiredness, necessitating a stop for a rest as occurred when travelling down to Sussex on our weekends off duty.

Sometimes if there was no indication of when I was going to return home in the night, Sara would ring the hospital switchboard to ask what was happening. The hospital night switchboard operator would arrive at his post at six in the evening and settle in with his hi-fi and chess set. The switch board was situated with a window overlooking the hospital entrance and so the switchboard operator saw everything and everybody who came and went.

Doctors would often play him a game of chess late at night and of course he had a feel for what was happening in the hospital and how urgent things were. All phone messages from the hospital came through the switchboard. He could tell by the urgency in the voice, asking for example to be put through to the pathology laboratory or to the duty consultant that urgent and sometimes critical procedures were going on. If Sara phoned to ask what was happening, he would say “Mr Maybury is just finishing an operation and should be home soon,” or “I think Mr Maybury is in the middle of a difficult procedure and may be a while.” When I did get home Sara would have tea ready and as always we caught up with the day’s events before turning in for the night.

We frequently had company at mealtime. One friend and colleague who visited was Julian Sansom, the surgical registrar at Stratford-upon-Avon hospital

Julian and I covered emergencies at each other’s hospitals when the other was off duty. One hot Sunday in summer I was called over to operate on a patient who needed an urgent laparotomy at Stratford-upon-Avon Hospital. The hospital straddled the cattle market in the town, so the patient had to be wheeled by trolley across the entrance to the cattle market to reach the operating theatre. It was very hot in the theatre, which did not have air conditioning, so I asked for the window to be opened and a cool breeze brought relief.

After a few minutes there was a shout from the anaesthetist and looking up I saw a cow was staring at us having stuck her head through the open window. The cow was shooed away and the window closed leaving us with three or four flies wheeling round the operating theatre light. Quick action was needed before they contaminated the open wound. Fortunately, the anaesthetist was resourceful and filled a syringe with ether and placing the finest needle onto the syringe used it to kill each fly in turn with a well-directed squirt of the anaesthetic agent. All the flies were so dispatched and there was no contamination.

One morning the Firm headed by Mr Marsh was doing a ward round and we came to a patient who had problems swallowing and a barium X-ray had shown her to have a very long growth of the oesophagus. We had moved away from the bed and were discussing what could be done, then Mr Marsh decided a Moussin-Babin tube should be pulled through the tumour to enable the patient to swallow liquids. I suggested a radical resection. Mr Marsh looked at and with a slight smile said, “Now you are a registrar you are entitled to an opinion, I have considered it and we will do it my way and gave his reasons.

I appreciated this approach because he had allowed me an opinion, then thought about what I had said and had not changed his mind. Next day at the operation he was obviously right as the cancer could not be removed, so we pulled the tube through the narrowing of the oesophagus.

Several years later I was assisting one of my chiefs at an operation, when it seemed as though he might be about to make a mistake, I said. “Do we mean to do that Sir”. To which he immediately replied, “Just testing!” and changed what it appeared he was about to do. I do not know if I saved the day or if he was seeing if I was concentrating, either way it was a good lesson.

When a consultant I always encouraged my registrars to have their say, which I always considered carefully, because occasionally decisions have to be reversed or revised due to changed circumstances or technological advances. Jokingly explaining to them that if a patient said; “Mr Maybury said you were to take off my head. You must query the decision before acting”. Usually the considerable experience of the older surgeon, in what is after all a craft, held sway and was proved right, but it gave the opportunity to change course and no patient ever had the wrong operation.

Mr Marsh often quoted ‘bon mots’ to me. In my book, “The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery1” is described an operation I was carrying out in the twin theatre next to the one where he was operating. There was haemorrhage and I asked the nurse to go through to Mr Marsh to ask for help. I heard him loudly say, “Let him sweat for a bit”. I did not hear the rest of the sentence but the nurse came back and told me that Mr Marsh had said, I was to put a pack into the operating area and he will be along soon. This I did and he came and showed me how to sort the problem out, so then I would know what to do the next time.

From this I learned two lessons. The first was that if all operations proceed smoothly I would never learn how to solve operative difficulties for the future safety of patients. Mr Marsh carried out many technically difficult operations at which I assisted and learned This is the inestimable advantage of the true apprenticeship, seeing the chief most days and assisting him on these occasions during four lists a week, in a calm atmosphere with continual discussion of all things surgical related to our patients. This was in addition to the lists I did myself.

The second lesson was rapidly learned, that if the going was difficult to stay calm and think logically and call your chief before doing anything damaging. Anxiety is inevitable in the profession and at times the pulse races.

In the seventies, recordings of the changes in the pulse rate of surgeons during operations of different complexity was studied. The results were interesting in that, even during simple procedures by an experienced surgeon, the pulse rate rose, while during difficult major procedures the pulse rate would soar. Therefore, controlled anxiety was the norm. Mr Marsh said he would not trust a surgeon whose pulse rate did not rise while operating.

He took me down to London to attend a conference and afterwards gave me some advice. People presenting work at conferences always produce their best x-rays and graphs. If you really want to find what is going on find the speaker’s registrar in the bar afterwards and see what he has to say about his chief, adding rather cynically that no surgeon is a hero to his registrar.

During my two years as Mr Marsh’s registrar, I was taught and then carried out a large variety of operations. Including the closure an open spina bifida, in a new born babies who was leaking cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) due to this exposure, making infection of the lining of the spinal cord and brain likely if not closed. In the first half of the twentieth century and earlier these babies did not survive. The condition can be accompanied by incomplete development of the brain and spinal cord and in these cases surgery was not carried out.

Following the operation there is often a build-up of pressure in the brain which will result in hydrocephalus due to enlargement of the CSF filled ventricles of the brain which in turn enlarges the head due to separation of the skull bones which are not fused at this age.

To prevent this occurring I was taught to insert a Spitz-Holter valve to drain the excess CSF from the brain via a tube run under the skin into the peritoneal cavity in the abdomen. These were satisfactory operations. Occasionally the valve which only allows the CSF to flow from the brain into the peritoneum and not backwards became stuck. It could usually be reactivated by pressing on the valve under the skin of the neck.

This experience of cranial surgery was augmented by looking after many serious head injuries from traffic accidents who were brought to the hospital being the only accident centre in South Warwickshire and at that time there was only one surgical registrar at the hospital and that was me.

Many times I placing six burr-holes in the skull of a road traffic accident patient, to search for and if present to drain a sub-dural haemorrhage. These operations could also necessitate raising a cranial flap or elevation of depressed fractures of the skull as necessary. There were no scans in those day so the decision to operate was taken purely on the history and careful examination alone. There were skull x-rays but these cannot diagnose intra-cerebral haemorrhage or oedema.

It was always very important to speak to the ambulance men who brought in the traffic accident victims. On several occasions the ambulance men told me that the patient was talking when they arrived at the scene of the accident and now before me was a deeply unconscious patient.

There patients clearly had a functioning brain immediately after the accident, so subsequently something had happened inside the skull to render them unconscious. Essentially there one of two reasons or both. They had either had an intra cerebral haemorrhage and or catastrophic cerebral oedema, this latter is rapid swelling of the brain, the cause of which is still not fully understood. If the cause was haemorrhage then there was a chance that surgery would help, if oedema was the cause of the deep coma then these patients were unsalvageable and would die.

On clinical diagnosis it was not possible to differentiate these events, so all these patients were taken to the operating theatre with a view to placing the six burr holes in the skull with and an added craniotomy if needed should haemorrhage be the problem. In many patient’s haemorrhage was the cause of their loss of consciousness and evacuation of the blood-clot, on one or both sides of the skull gave the patients the best chance of a full recovery. Unfortunately, if on placing the first burr hole the internal pressure on the brain was so great that brain itself exuded through the burr hole, then there was nothing further to be done. I would then go to speak to the relatives who were naturally shocked by the accident and needed as gentle handling as possible, but had to be told the dreadful news.

Some surgeons feel guilt at this point that they could not do more. If everything had been done, that should have been done, then I could speak to the next of kin calmly without angst. I felt sorry for them and explained slowly, allowing the relatives to speak freely, while telling them of the terrible outcome of the injuries. Then if they wished, going through what was known of the accident, the diagnosis, the operation findings and their tragic and unhappy significance of brain death. In these circumstances, when there is no hope of recovery, the relatives must understand this, however long it takes to gently explain. These explanations also help the doctors and nurses who need to look after the patient during the brief time until death occurs.

For a very short while I toyed with the idea of being a neuro surgeon, but decided against. I enjoyed urology and was not put off by abscesses full of pus or other infections or the malodourous contents of surgery on an obstructed colon. I was firmly focused on the prospect of being a General Surgeon, even though the training was the longest of all the then specialties. On average trainee general surgeons were being appointed as consultants at on average forty years of age or more, but were rewarded by a wide variety of interesting work1.

Just before we left Warwick on going to the local fish and chip shop to buy supper, a nurse was also waiting to be served who had on a number of occasions baby-sat for us. Then to my surprise another identical young woman came in. I had never known that Rose had a twin and on chatting to them discovered that they had both baby-sat for us, they were the most identical of identical twins that I had ever seen with exactly the same voice and as far as I could gather they had shared the job of a single nursing post as well as the baby sitting. We all had a good laugh at my ignorance for not knowing and not noticing.

To complete the job requirements to ensure broad experience before being eligible to sit the examination for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS), I switched to be the orthopaedic registrar at Warwick Hospital for a few months and then took a fortnight’s holiday. The first holiday since starting work in Warwick. This quiet fortnight in Sussex reading for my examination served me well and a short time later, the examinations behind me I was elected a Fellow of the Royal College Surgeons of England. The date was 1972.

While at Warwick I learned the craft of surgery from John Marsh, it was the best of jobs. Now I was advancing, in the surgical sense, towards becoming, “All things to all men1”, at a rather earlier stage in my career than anticipated.

Reference:

*The End of the Golden Age of General Surgery 1870-2000. The Training and Practise of a General Surgeon in the Late Twentieth century. Publisher: Createspace. 2015 ISBN 1499531370. Ch. 2. Page 11. Available on Amazon.

CHAPTER 5: Back in London.

I had applied for the job of Post Fellowship Registrar at the Middlesex Hospital*, which was next to Soho in London. The post of surgical registrar was advertised to work for Mr Cecil Murray and Mr William Slack, later knighted, who were the consultants of one of the general surgical firms with a particular interest in endocrine and colo-rectal surgery respectively.

On entering the imposing lobby of the hospital I noticed a beautiful Queen Anne table** in the centre which was deeply inlaid. The table was generously proportioned being about eight feet across with a splendid pedestal support. It had a magnificent bowl of flowers in the centre which were daily refreshed by the Friends of the Hospital.

I asked the porter for directions to the interview room and found the waiting room already occupied by a number of other candidates some of whom I knew. My spirits dropped but I did not allow it to show and was much surprised after all the interviews had taken place to be called back in and offered the job. I accepted with pleasure and was expected to start work within a month.

Sara put our house in Warwick on the market and were kindly invited by friends of my wife’s parents to stay once again in their Oast-house next to Brightling Place, in Sussex.

Life for the next three months at Brightling Place could not have been better. I caught the train from Robertsbridge every weekday while Sara enjoyed her days at the Oast-house. It was while we were living there that it snowed heavily and for the first time in my working life I could not go to work. For three days the snow was so deep that the road to Robertsbridge Station was impassable, making it impossible to catch the London train. I felt very guilty about not going to work but it could not be helped and I enjoyed the time at home.

One weekend during our stay in the Oast house we went to London to look for a house to buy. In the Evening Standard that Friday evening there was an advertisement for a small terrace house in Bellamy Street in Wandsworth. At that time the housing market was overheated with rapid price inflation and there was now a house buying frenzy. Knowing that speed was of the essence to secure a property, I immediately drove over to see this house. It was a tiny two up and two down Victorian house, built probably in the eighteen-eighties in a long terrace sweeping down a hill with a matching terrace on the other side of the road. It was charming and at the back was a garden seventy feet long with a splendid silver birch tree and flower beds overflowing with roses which grow so well on London clay.

On entering the house, I found that there were already four couples there looking around. There were no cell phones in those days so I left immediately and rushed back to collect Sara and half an hour after leaving the house we were both looking around the house. There were still four couples in the house looking around. It took Sara about two minutes to decide that this was a house we could live in and enjoy. Quickly finding the owner we immediately offered to buy the house at the asking price and gave him a cheque for ten percent. The price was eleven thousand pounds. We had taken advantage of knowing about this buying and selling frenzy in the housing market and a few days earlier had arranged a mortgage in principle and a loan for the deposit from the building society.

With cheque in hand the owner accepted our offer and the deal was done. Sara and I had never taken more than a few minutes to agree on all our major purchases in life. We were very pleased with the house and some two months later the purchase of 42 Bellamy Street in Wandsworth was complete and became our favourite house. No survey was done but as all the houses the street appeared to be in a good state, all having their original slate roofs with no evidence of sagging or cracking of the brickwork. Perhaps the most notable thing was that the house was affordable and the mortgage needed was less than three times my salary. This was insisted upon by the mortgage company and evidence had to be presented that the salary quoted was real by having a payslip scrutinised. We left the Pepys’s with great regret but were excited that we were moving into a house of our own again.

Before the Second World War Bellamy Street had been a street of artisans with their families. Our next door neighbour, who had lived in the street from that time, told us that the street used to be bustling with activity, while the men were out at work their women folk were busy about their daily life, which included socialising, popping in and out of each other’s houses, while the children played in the street. Now twenty-five years later, in the early seventies, the street was empty during the day.

The nearest underground station was Clapham South on the Northern Line, only a short walk away and took me directly to Tottenham Court Road Station in central London. This short journey often took over an hour due to the overcrowding and irregularity of the trains in those days. The walk from the house to the tube was initially depressing, due to rubbish and dog waste on the pavements. After a few months I had stopped noticing these unpleasant intrusions into daily life and got used to reading on the tube either sitting, a rarity, or standing.

In Warwick I had been on duty virtually all the time, but lived at home one hundred and fifty metres from the hospital and went home if there were breaks in the work. The Middlesex Hospital being in the centre of London was very busy by day, but as all the commuters left for home it became very quiet, with very few emergencies for the duty surgeons to look after or operate on. It is a truism, that when there is little to do, the inclination is to do less. So any emergency was more of an effort to get on with. The surgical registrar rotation was that I lived in the hospital one week in four.

However, my time was well spent at the Middlesex. My reading of surgery deepened and there was time to consider diseases and operations in depth, with regular clinical seminars and attendance at medical conferences, especially the Association of Surgeons and the Surgical Research Society. It was an enjoyable time in a very different way from the total absorption with continuous operating lists and emergencies. A slower pace now with more contemplation to redress the balance in my training, but at the expense of some boring times when resident in the hospital, with little in the way of emergencies to look after. Even this gave me the time and opportunity for more reading which I gladly took. The surgical disciplines in which I had the opportunity to advance at the Middlesex Hospital were endocrine and colorectal